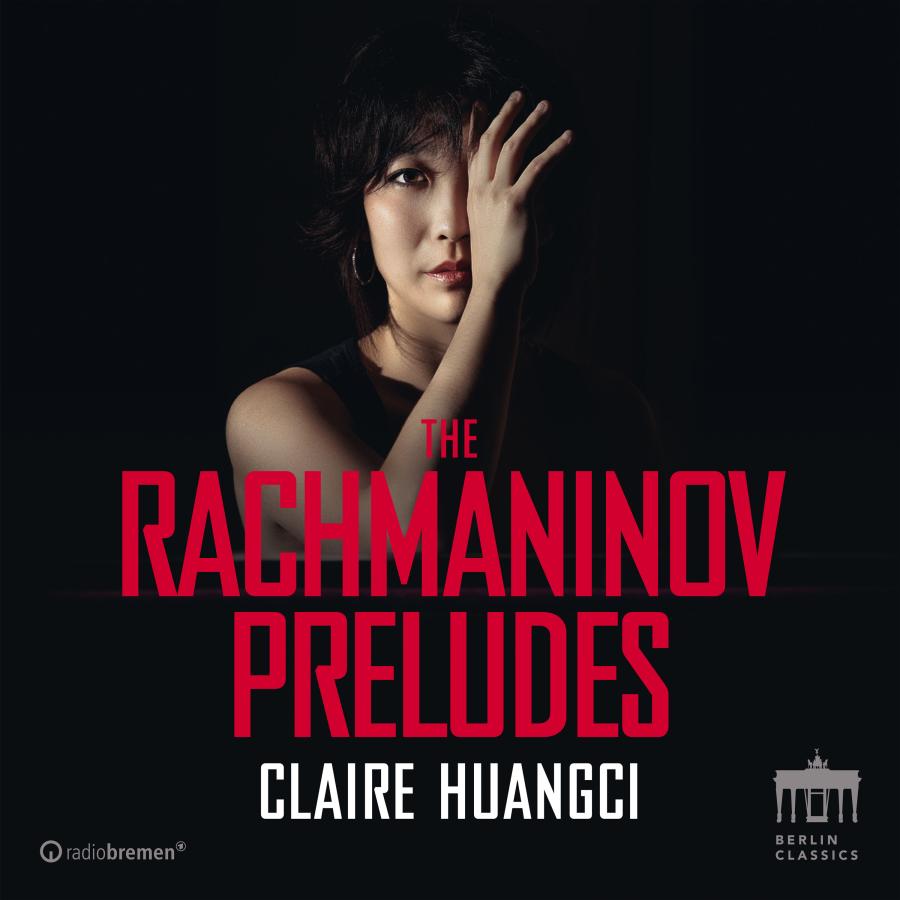

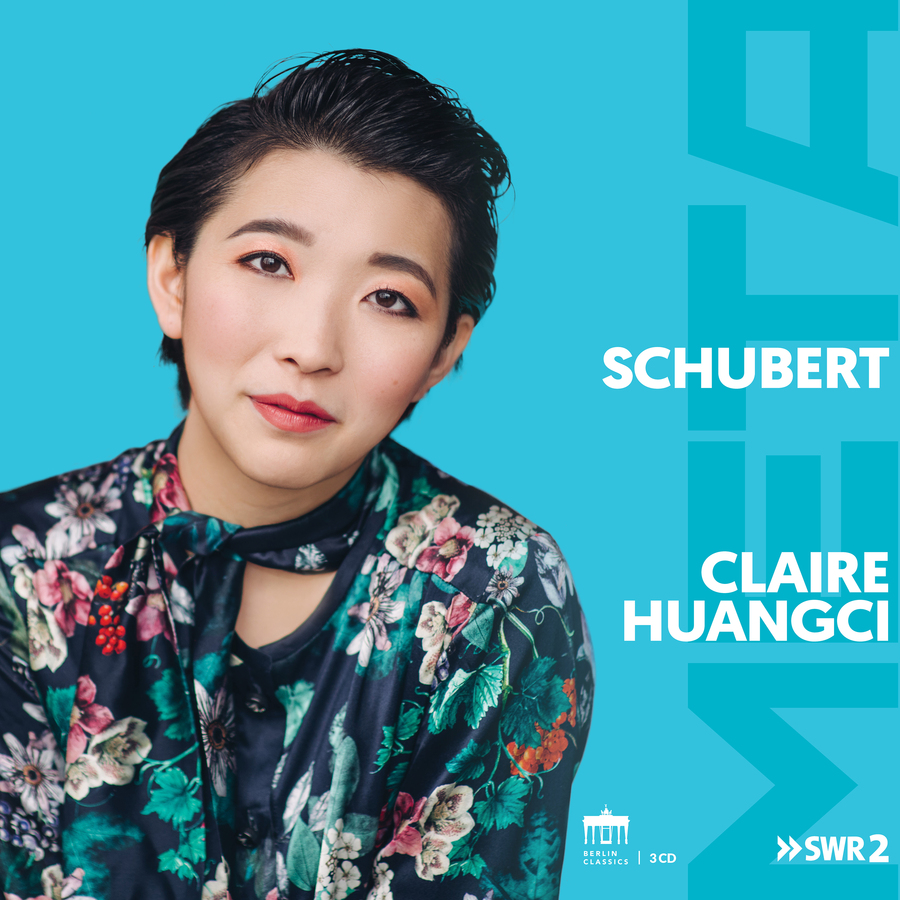

Following on from her last, highly-acclaimed release of all of Chopin’s Nocturnes, the Chinese-American pianist Claire Huangci now takes on the next pianistic giant from the other end of the Romantic spectrum: Sergey Rachmaninov and his 24 Preludes.

Claire Huangci explains that in recent years she has felt herself more and more attracted by entire cycles of works, “in order to better understand the longer spans of an individual composer’s life.” In the case of Rachmaninov and his 24 Preludes from three opus numbers, the challenge is very interesting, since he composed them over a period of 18 years. In 1892 Rachmaninov laid the foundation stone with the Prelude in C sharp minor op. 3 no. 2, which soon became one of his best known works. Remarking on the fact that audiences called for it time and again as an encore, the composer said in 1921 that “I much prefer other preludes.” That is understandable, when we take into account that this particular prelude was constantly associated with extra-musical “programmes”. As Claire Huangci says: “If we are to fully appreciate the psychology of the prelude, then let us agree that its function is not to express a mood, but to precipitate it.”

If we transpose that concept to all of Rachmaninov’s Preludes, then this statement makes it clear that the diversity of emotions that Rachmaninov wished to convey was vast. The ten Preludes op. 23 of 1903 and the 13 Preludes op. 32 of 1910 complete the double dozen and clearly outline the Russian composer’s evolving intentions: “You can hear the transition. Rachmaninov’s music became more complex, more contrapuntal; it became harmonically more interesting and more exciting,” according to pianist Alexis Weissenberg.

Claire Huangci, once hailed as a child prodigy, who most recently won the Concours Géza Anda, one of the toughest piano competitions of all, “has developed into a mature artist,” the jury concluded. Still in her twenties, she has already established herself as a popular pianist, giving concerts from China to the USA. The fact that she has now turned to this pinnacle of the late Romantic piano literature illustrates clearly both her consistent self-expectation with regard to her pianistic performance and her interpretational maturity. Even if one or other prelude may seem “to have added a devilish twist to the most challenging of Chopin’s and Liszt’s preludes,” they are for Claire Huangci not simply technical practice pieces, not just a way of showing off her pianistic skills; they reveal the true core of Rachmaninov’s character: “a symbiosis of modest purity and the most filigree virtuosity.”